Life, no matter where it is lived, resolves itself into routine or, otherwise, never really becomes “life.” Three months in, the contours of my routine have become fairly clear. The life of an ex-pat in Xi’an revolves around a few bars and clubs, perhaps language classes, a girlfriend or boyfriend if you have one, work and shambling about. It’s almost painfully normal. The appeal then, is not the day-to-day minutiae, but rather the thrum compressed human energy that surrounds it.

As my life has no ready-made narratives these past few months, please accept the following short takes:

Outdoor Life

I grew up in a place where, if you asked someone what she did in her free time, she’d probably say walk on the beach, see the sun set, or work in the garden. In contrast to that, the routines of city life could not but be more glaringly different. Yet, even with such caveats, free time in China can sound rather depressing. Ask a man how he fills his time and he will say videogames, movies, and nights out with his friends. As a woman and she will say shopping and hanging out with friends.

Again and again Chinese tell me that their country is restrictive, not politically (they don’t care much), but socially. They speak of the pressure from family and friends to conform. Chinese daily life—at least in the cities—is based on family, friends, and work. Often these are one and the same. Chinese people seldom seem to be alone in their free time. If a Chinese person is alone, he is often running an errand or waiting to meet someone. Few activities seem to occur outside these bounds. It’s easy to see how this weight can bear down on them—there is little respite from friends and family—from people who know you and have expectations of you. The escape to videogames seems a very logical result.

Yet the fact remains that Chinese do hang out together and, unlike in the states where activity is largely confined indoors, life in China is conducted outside. There are food stalls and clothing stalls everywhere. Numerous shops lack doors and simply open on to the street. To be out is to be surrounded by activity. I can only imagine the shock new arrivals to American cities must feel when confronted by the relative lifelessness.

The Neighborhood

My apartment block is located down a back street, only a block and half from the city center and yet, despite the small distance, you’d never know.

Our house has a gate-keeper, a shiny bald, wrinkled old man who lives in the tiny gate-room with his wife. His day often consists of watching television and separating out the apartment’s trash into to two burlap sacks. Often a girl—a granddaughter perhaps—hangs out with them.

Directly outside the gate is some sort of scrap metal collection site. During the day, men go at large pieces of aluminum or motor-part-looking contraptions with hammers, breaking them down into component parts. They operate out of a little garage and, at night, a big truck is parked in front and loaded fifteen feet high with scrap metal.

On either side of the garage are hair saloons and more further along the alley. Whereas many back alley salons are merely brothels, these are the real deal and are constantly in operation—as in Istanbul, barber shops and salons stay open until ten o’clock or later. In one direction along the alley way are more apartment blocks. In the other, in addition to the salons, are a number of little restaurants, unmarked and outwardly caked in dirt, but overflowing with customers during the lunch hour.

At all times of day, the street is busy. Children run to and fro, small dogs—the occasional collie is the only large dog I’ve yet seen—patter about in little knitted vests and men fix bikes and motorized rickshaws or play badminton with their wives.

In the morning the main road is full of vegetable vendors. Small hot peppers, bok choy, various other leafy greens, bean spouts and tomatoes are common—as are the dark-orange verging-on-red carrots that are ubiquitous in China. During the market times, the street is a chaos of vendors, buyers, bicyclists, motorcyclists, rickshaws, car drivers honkingly oblivious to the narrowed streets, and random passersby.

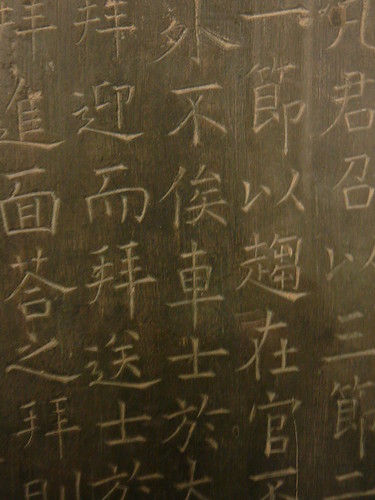

Head the other direction, past those other apartment blocks, and you emerge on a main street lined with shops. Here are the majority of restaurants I go to as well as a dog-groomer, a sign-carving company, more salons, the entrance to a parking garage, several repair shops and multiple videogame parlors.

In the daytime, this street and, frankly, every other in the area, is rather depressingly scruffy. But this all changes at night. In the dark, the dirt becomes invisible and what stands out are the neon lights and the activity. Most nights, I get noodles on the street and sit watching the passersby, listening to shouts from nearby mahjong tables, and lose try to let the moment last forever.

Practicalities

Then there is the issue of bathrooms. Bathrooms in China are almost all squats. The only exceptions are places which cater to western tourists. Stalls do no have toilet paper or—unlike Turkey—a bucket and tap. Stalls usually have doors, but seldom have locks. Moreover, they aren’t cleaned regularly, the surrounding floors are covered in uriny-water—the floors outside are too. Often the foot flushing mechanism breaks or goes unutilized for multiple uses; the result is a large pile of shit waiting to greet you upon entering the stall.

If any of this sounds disconcerting—and I’d imagine it does—I’d say you’re thinking about it wrong. This is simply the way it is. If any of the foregoing details sound disgusting, consider that (contrasted with the US) China at least has public bathrooms all over the place. Very seldom do you have to pay for them. The only expense that falls on you is the cost of a pack of Kleenex.

And bathrooms are representative of a more general fact about China: It is what it is and complaining get you nowhere. Time and again people whinge about the following problems:

- Spitting. People spit everywhere. On the street, in the midst of vegetable markets, on buses, upon emerging from bathroom stalls, in restaurants and on the carpet of Starbuckses. Likewise, men are constantly pushing closed one nostril and rocketing out jets of snot from the other. These hygiene issues extend to person grooming including nail clipping in the middle of restaurants, cafes, offices and teachers’ rooms. When you consider that a good part of The Stranger’s “Last Days” column is given over to gripes about such things, you realize how uptight Seattle truly is . . .

- Driving. Chinese are amazing drivers—though few agree with my assessment. They weave in and out of traffic, pass pedestrians and bicyclists with only inches to spare and drive on sidewalks if necessary. Someone one in America attempting such stunts would be dead within days, yet most Chinese are verifiably not dead. Pedestrians don’t help matters by walking out into traffic given the slightest opening. Unlike the US where we let lights do our thinking for us, the simple act of crossing the street in Chinese forces us to be fully aware of the surroundings.

- Slow Service. In Turkey, I rather enjoyed the slow pace of service I received because it often seemed as though the staff were enjoying itself. At government offices, the officials would drinking tea, chat and, intermittently, attend to your paperwork. The might, if the mood struck them, start up a conversation with you. Chinese office slowness seems less lighthearted, but it is equally lugubrious. (And this is strange because it seems to aggravate Chinese as well. Whenever I find myself in a line with a Chinese, he or she constantly pouts and harrumphs about the pace of the clerk.)

- Haggling. The price in China—in much of the world for that matter—is not the price. I vividly remember, back in Seattle, going over the cost of products I ordered for cafes and restaurants and wincing at how small our profit margin was, but in the US the idea is price competition. The price is the price and if people don’t like it, they will go elsewhere. In China, price is merely a starting point and every major purchase becomes a game of chicken. My suspicion is that, this business model helps explain why developing countries can have twenty of the exact same store lining a street. Once the choice of store becomes a matter of best deal and other considerations (such as family connections), it becomes more convenient for all the stores to group together. Were thirty plumbing supply stores spread throughout the city, people would just go to the closest one and settle for its prices. If all the plumbing stores are beside one another, the customer can make his way up and down the row, negotiating the best deal.

I don’t want to imply that I never complain about these things. Rather, I mean to say that the complaints are pointless and, if these sort of things are insurmountable difficulties, China is not the place for you. One has to ask himself what truly matters, what he can live with and without.

Entertainment

Xi’an has a good number of bars and clubs. Most teachers frequent one called the Park Qin in the basement of a hostel. The place is darkly lit—some might say cave-like. Next door is another, slightly seedier, hostel-cum-bar called the Shuyuanmen. Finally, right beside the central Bell Tower, is yet another dingy-but-popular hostel/bar. This last one gets the budget travelers and, less explicably, all of the city’s teenage lesbian population. A good night there involves an hour of pool, cheap drinks and a constant stream of girls dressed like K.D Lang passing by.

While Park Qin gouges you with its high-priced, watered down drinks, the rip off is at least muted amid the grotto-dark colors. Along neighboring Bar Street, the tourist squeeze is more blatant. And, of course, all this is relative. A beer ranges in price from ($1.50 to $4.50 at the most expensive place). A cocktail is typically ($2-$5). No worse than a dive bar in the states—except that teachers only pull in about $200 a week.

You feel the pinch more at the clubs. There are several and they are decidedly mixed affairs. Take 1 + 1, for example. The place has at least three sections; a crowed dance floor surrounded by tables and recessed rooms full of couches where you can be waited on in style. Down on the dance floor, a press of men dance, dry ice is pumped out in clouds, more exhibitionist sorts dance up on elevated blocks, and pity be to any girl who enters the dance floor not expecting to be pressed up on immediately by a half dozen Chinese guys. Especially on this floor, you see groups of men, tables covered with beer bottles and, scattered here and there, drunken People Liberation Army (PLA) officers.

More sane is the upper dance floor which, for whatever reason, is calmer. The dance floor is smaller and girls are able to dance as they please without fear of groping. This is where the foreigners seem to congregate—Saudis, Pakistanis, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Dutch on vacation, students from assorted African countries.

(And if neither of these are not your cup of tea either, there’s a lounge area where you can sit and revel privately in your wealth. Again, I suspect this is for the truly well-heeled, those still suffering from a degree of status anxiety would be out on sight, displaying their money.)

Now, all of these places have a dark side—anywhere in the business of getting people drunk does. The Bell Tower hostel will have bottle-breaking fights between furious lesbian lovers and I have witnessed two occasions of a Chinese guy feigning to choke his girl friend at 1 + 1. Outside these places one can expect to see angry arguments, many of which are uncomfortable to watch as an American. China is one of those countries where women (not all, but these is great truth to the following generalization) expect their boyfriends to show an aggressive, frightening level of jealously and where, to do otherwise, would be considered a sign of gross indifference. The result is these mutual, public screaming fits.

And yet, for all this violence and seediness, all these places in combination have a narcotic effect. To move from one beat-pulsated bar to another is to feel as if the everyday world has been stripped away to reveal something more subterranean and magical. To know, sitting around on a given night, that people are out somewhere dancing and living it up, that there is this well of vital energy out there which you can step into if the urge strikes, is a powerful knowledge indeed.

This is the danger of travel in miniature: Knowing there is so much more out there than you can take in with your senses at one time; knowing that so much is happening at once, and knowing that you must choose between it all.

How does one keep himself down on the farm after he’s seen Xi’an?